What does Human Centered coffee production mean to me?

The weakest link in the supply chain is also the strongest one.

The Valley of Nebaj in Quiché, Guatemala. October 2006.

When I was growing up, my father thought that I had to get to know every single municipality in my country, Guatemala. At first glance, this seems like a feasible idea, even an exciting idea. But in the 90’s Guatemala was still a very remote country, severely underdeveloped, most of it with precarious or even non-existent infrastructure, and living through the last wave of the Civil War.

This was not just about the geography and the numerous paradisiacal landscapes. This was also about the people. About 76% of the population is divided into 22 ethnic groups of Mayan descent, each with its own language, its own customs and traditions, and, as I would learn years later, with their own particular ways of going about business.

My favorite place was –and is still to this day– Panajachel, a small town located on the shore of Lake Atitlán. Or “The Lake”, as tourists call it. About 18km long and 8km wide (11.2 x 5 miles), a maximum depth of 340 meters (1,120 ft) makes it the deepest lake in Central America. It’s framed by three stunning volcanoes, all higher than 3,000 meters (10,000 ft), and surrounded by lush forests in every direction. It’s not only my opinion that this lake is beautiful. Alexander von Humboldt literally called it “the most beautiful lake in the world.”

Panajachel is an absolutely magical place. It’s decorated with some of the most amazing sunsets I’ve ever seen, and also with the most diverse of populations, as uniquely colorful as the sunsets themselves. This is the place that congregated most of my extended family.

Visiting my grandparents was a whole different story. They lived in the eastern part of Guatemala, which is as hot and arid as a land can be without being properly a desert. Just as the environment is different, life is also different. In this cracked and dusty soil, the vegetation is very peculiar, often more brown than green and full of huge thorns. There are always vultures flying high against the sun in circles.

These two were the most recurrent places. From here we would make camp and move on to other more remote areas that could only be described as part of a fairy tale book. I spent all my childhood and adolescence going on these expeditions.

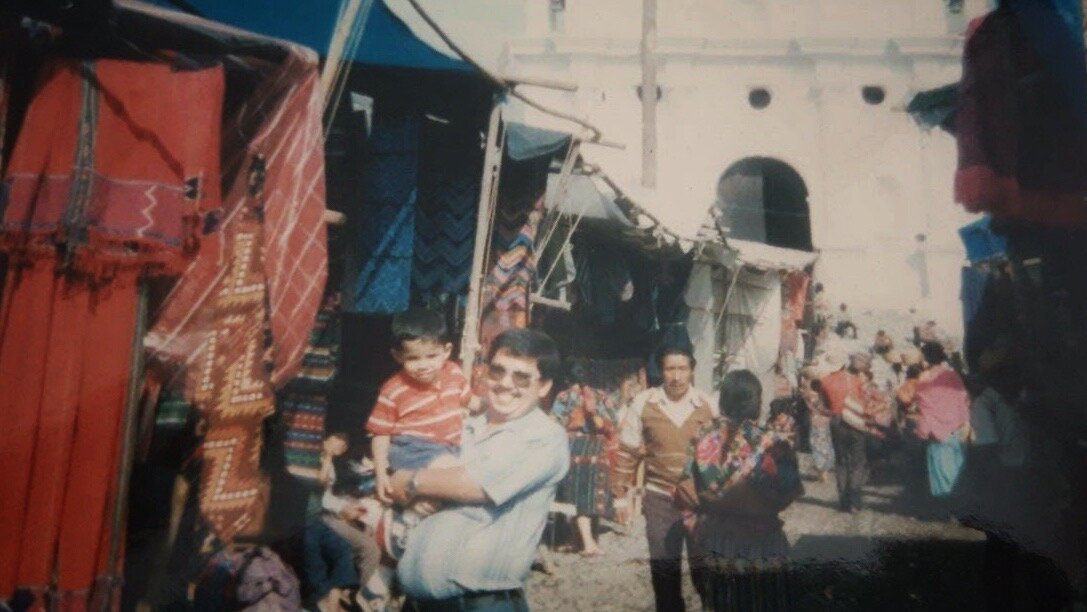

My father and I at the market of Chichicastenango in Quiché. Guatemala, 1989.

When I reached adulthood, I was very familiar with even the most remote places in my country. I knew how to find and drive through the most incredible secret roads. I knew how to maneuver through the many extreme microclimates that change drastically from one kilometer to the next one.

But living all these experiences meant much more than just appreciating the astonishing scenery Guatemala has to offer. It meant experiencing how people live in each part of the country. It meant hanging out with locals in each town and sitting in the square just watching time go by. It meant having dinner and chatting long hours at the tables of friends and going to mass with them on Sundays. It meant experiencing and learning how differently the very same activities were carried out between one place and another.

It involved talking to people. A lot. Asking for directions. From how to get to a place, to where to catch the sunrise or the sunset. Listening to stories and legends. Paying the most careful attention to the advice given by the elders.

I discovered that this small country was a very big world.

One of the last places I visited was the northern part of Quiché. Perhaps the most severely hit by the terrors of the Civil War, where the worst of the massacres had occurred. The type of unspeakable contradictions that make these lands cry tears of blood.

I had read about these places in history books and in reports from the United Nations. The names always seemed to me like places that had been ravaged by war and were deserted to the point of being wastelands.

To my surprise, places like Cunen, Salquil, Acul and the whole region known as The Ixil Triangle, formed by the towns of Nebaj, Chajul and Cotzal, are among some of the most exuberant and breathtaking places I’d ever been to.

The drive to Quiché is a rollercoaster. Up and down the most complicated road in the country, with its sharp turns barely hanging from cliffs, with potholes in every section of the way, and, now and then, tons of pouring rain. At some point you reach Sacapulas, which is so low in altitude that it feels as if you’re in a beach town in the middle of the mountains. From here it’s all uphill into the clouds.

I would drive this road on a Friday afternoon. Feeling how the weight of the “things of the City” gradually stayed behind until they disappeared completely. Ten to twelve hours later, depending on the weather, I’d be sleeping in Nebaj.

On Saturday, the noise of a very busy street outside my window would wake me up. After sunrise, under the faint but constant rain, I would walk two blocks down towards the square to have breakfast, down the steps in a corner into a diner called Comedor Elsim.

One of the strongest impressions I have of Nebaj was coming out of this comedor, thinking already about the drive back to the city, when I saw a large group of people gathered in the middle of the street. There was a man holding a stick in one hand and a rattle toy on the other. In front of him, on the ground, was a brown piece of cloth. The crowd was absolutely silent as he danced around it in circles holding the stick and rattling the toy. Underneath the cloth was a snake. As the serpent enchanter whistled there was thunder in the distance. Downhill, a tent was being set up. The circus had arrived in town. The year was 2005.

I felt a strong affinity towards the Ixil people I had made friends with. The leader of this one group, called Joel, had told me how he survived two massacres while he was still only a kid. He was always looking for ways to do business and bring projects to his community. A sense of community that can only be understood in light of the terrors of their past.

Once a month I would drive up to Quiché with my father, who is still to this day my guide and companion when going to these difficult places in Guatemala. We would have meetings with a group of people who were trying to get organized to form a Cooperative so that they could be beneficiaries of some government program.

This was my first attempt at working with a community, and my intention was to document how many members they had, where their parcels were located, how many coffee trees they had in these parcels, and how much coffee was produced.

This was also the first time that I was trying to adapt my Coffee Traceability System to follow collective decisions instead of the individual decisions of single producers.

As I interviewed them, with a translator interpreting my questions, my father would snap their portraits, one by one, and we would make them name tags as a symbol that they were part of the project, although the pictures were mainly visual aids for me so that I could remember their names.

Portraits of Members from the Ixil Community in Nebaj. November 2005.

The idea was simple: if my system was working on larger farms to trace the samples back to their handling, back to their harvesting, and even back to the growing of the coffee trees, then it would also work for a group of producers if I treated the Cooperative as a single large farm and I just added one additional line to register who the individual producer was.

With my system in place, I would have all the information necessary to advise each producer individually on how to improve their practices so that their samples would result in a better taste of the cup. With time, they would end up delivering beans of such a quality that I could roast them to an extraordinarily above average cup quality, just like I was doing with the larger farms.

(Read: What does Specialty Coffee mean to me?)

I’ve always preferred working with people with whom I have a strong friendship. The relationship was there. I’ve always preferred working with people that are eager to learn and to excel. This hunger was there. We had spent months planning and getting ready to solve any issues that might arise along the way. The preparation was there. My Coffee Traceability system had been adapted to their Cooperativa. Everything was there!

Harvest came and not a single coffee sample was sent to me.

By the time I went back to the mountains, all of the harvest had been sold to someone else.

Sitting with them at Comedor Elsim, I was trying to have them explain to me what had happened. We had spent nearly a year working together so that in the end I would receive their samples and I could taste their coffee. And in the most critical moment of the whole process, nothing happened.

What went wrong?

All along the way, I had been paying attention to how to make things work. But I had overlooked how people work.

These people had learned for generations to act from fear before anything else. So when a swiss guy came to the community waving the Fair Trade flag and offering to pay sub-par prices up front, they sold. They sold everything. They sold everything to less than half the price that I was offering to pay because they were not comparing prices. They could only put certainty on the scale. And with only certainty on their minds, a very low price up front was undoubtedly better than the promise of a higher price that I had offered to pay at the end of harvest.

Up to this day, I still consider my project in Quiché to be my biggest failure. But it’s also the failure from which I learned the most important lesson of my professional career: things will only work if you truly put yourself in the shoes of the people that you’re working with. Not just a bit. All the way! Until the point where you deeply understand their feelings and emotions and take care of that first.

After you have taken care of their feelings and emotions, then you can take care of their interests. Then you can talk business. Then you can start doing business, and actually succeed.

It’s only after you have taken care of their feelings and emotions that each and every one of those individuals become the strongest link in your supply chain.

What does Specialty Coffee mean to me?

I started in the Specialty Coffee segment of the industry. The funny part is, back then, I didn’t even know what Specialty Coffee was.

I was in the Specialty Coffee industry before I even knew what it was.

The Roastery at San Marcos El Tigre. La Terminal. Ciudad de Guatemala.

My name is Josué Morales and I have been in the coffee industry since 2003. I started in the Specialty Coffee segment of the industry. The funny part is, back then, I didn’t even know what Specialty Coffee was.

Back in the day, I was just a nineteen year old kid. I was in my second year of university and I had a job at the City Hall of Guatemala City, which was a dream job for someone my age.

I’ve always had a knack for trading. Buying and selling stuff has always made me happy in a way that no other profession could ever do. It was through that window of thrill that coffee came into my life.

Every day, during my lunch break, I would take a bus from the City Hall to the God-forsaken market called “La Terminal,” which is the place where most of the city’s businesses have sourced their produce and supplies for over a century.

“La Terminal” is a place like no other. With its crowded streets so full of people that cars can barely move. I walked the dirty streets under the midday sun blazing on top of my head, full of noise, smoke, and the smell of rotting fruits and vegetables filling up the air. On rainy days the heat and the moisture made the smells so pungent that it was hard to breathe.

The crowd. The smoke. The noise. The filth. It was definitely the worst place to be for the senses. But it was also the pulsating heart of the city. It was exploding with life. A majestic dance of vitality. I fell in love with it.

I would get off on Segunda Calle and walk about twelve blocks into the far end of the market to a place called “Comercial El Éxito.” At the end of its narrow street I would find a roastery called “San Marcos El Tigre.” This is the roastery that I had hired to roast and package the coffee that I was selling.

Upon entering the shop, the crackling sounds of their ancient roasting machine would greet me by spitting out the smoke that lingered in the air once coffee finished roasting. It was here, at the foot of this machine, that I discovered that working in coffee made me happy.

The roasting machine at San Marcos El Tigre.

I acquired the fondness for the sensation of holding the shiny roasted beans in my hands. It was also here, in this roastery, that I met the first coffee producers that helped me get started with my own business.

These coffee producers were here purely out of tradition. Their parents had brought their coffee to be roasted here and their parents before them. They would come at the end of harvest to roast the coffee they would drink at home during the rest of the year. We probably ended up coming here because of the same reasons, upon calling all the roasteries listed on the phone book this one offered the lowest price.

I made the best imaginable use of this tradition. While I was there, instead of minding my own business like everyone else did, I got the producers permission to pull out small samples of their coffees. I brewed and tasted it with them as we waited for their coffee to be packaged.

I can clearly remember when Ovidio, the owner of “San Marcos El Tigre”, allowed me to set up the most precarious tasting station on a tiny corner of his desk.

It was here, in this negligible tasting station, improvised on the corner of a messy battered desk, where I started discovering taste.

The taste of coffee would differ from one region to another; from one farm to another. Even within one farm it would be different from one batch to another, and the very same coffee would completely vary its taste if it was roasted at a different temperature.

Having grown up in a producing country, most of what I had tasted before was second and third grades of pre ground and pre blended coffees. The coffees that I was tasting on my little corner of that desk were something completely new to me. They were exciting.

Fast forward one year and I was opening my own roasting business. I had landed a couple of fairly good accounts and I had somewhat of an idea of how much I needed to be making to keep my startup afloat.

My financial situation wasn’t strong. I was only able to buy from producers who would give me credit.

Doing all the manual labor triggered my imagination. It allowed my obsession with numbers and my obsession with measuring to be able to register everything.

I personally received each and every bag. I personally roasted each and every batch. I personally packaged each and every pound. I personally delivered each and every order.

The unavoidable result was that I got to know each and every coffee very, very well, to the point that I was able to detect even the slightest change in taste and appearance.

There were variations from one batch to another, from one delivery to another, and even coffee that was delivered on the same truck sometimes looked, smelled, and roasted differently. These variations were something that I never saw coming. They keep messing with my mind till this day.

I tried to make sense of these variations with every resource that I had at hand but nothing really worked. Nothing that I tried really meant a thing. And believe me, everything that you can imagine, I tried. Multiple tests batch after batch, day after day. But nothing that I did was helping me develop the right metrics to understand the changes each coffee presented.

I got to the point where I was disappointed with myself because I couldn’t explain these variations. I was hitting a dead end. In my sleepless nights I figured it out, it became evident to me that there was one thing and only one thing that I could do to figure out what was going on.

I had to go out into the fields.

And so I did. I went out on a research expedition to find out where the variations in taste came from. Reconnecting with my friends, the producers that had helped me this far was the starting point of understanding. The only things I took with me was a notebook, a sleeping bag and my obsession with measuring, registering, and documenting everything.

But how do you recognize the variables that affect taste out in the fields? How can you tell from looking at the plants? How can you tell from watching how the people handle the coffee in each farm?

For the purpose of my initial research, it was very lucky for me that the producers I worked with weren’t many at the time. I visited each and every farm, from the high mountains of Huehuetenango, to the lowlands near the Pacific Coast, and everything in between, including the very special regions of Antigua, Palencia and Atitlán.

I walked each and every path, and shook the rough hands of each and every coffee picker that touched the coffee beans that I was buying.

Nineteen year old Josué Morales. Finca Montes Eliseos. Guatemala.

Yes, I know, probably most of this work was not necessary, and it had been done before by many others. But my obsessive mind made me go through each and every detail of the whole process, and it made me document it.

From the individual trees and their health, to the harvesting and the quality of the selection –WHEN was the specific day that each bean had to be harvested, or not– to the handling and the shipment of each and every single batch that I bought, so that in the end, I could trace the taste that made each coffee unique back to its handling, back to their harvesting, and even back to their development on the coffee trees.

Before I knew it, I had created a system that could trace the occurrence of any specific taste back to the whole process that was behind it.

This personal and exploratory research made me aware of how each step of the process of producing coffee could affect its taste. I got to the point where I developed a taste of the farms. Just by looking at how the people were taking care of the trees and how the people were harvesting and handling the coffee I could tell what the result would be in the cup.

The taste of the cup, I discovered, always came down to the actions that people do along the process. And my obsessive-compulsive mind made me register, document, synthesize, and analyze all these actions.

Based on that, year after year, I started guiding producers away from the practices that would end up in tastes that were less desired by my customers and closer to the practices that would end up in the characteristics that were more greatly desired and rewarded.

I was orchestrating a very complex process involving many different people in many different circumstances in such a way that they would end up delivering coffee of such quality that I could roast them in extraordinary ways.

It was years later that I learned that the things that I was doing had a name. The process of documenting where each coffee bean comes from and how it has been harvested and handled is called Traceability. And the pursuit of the best quality in the cup, to which I’ve dedicated my entire adult life, is referred to as Specialty Coffee.

Learning these words has not changed the meaning I assign to my work. One thing is how Specialty Coffee is defined. A much different thing is to realize what it means to me.

I personally know the owners of each and every one of the farms I buy coffee from. I have been in those farms. I have eaten at their tables. I have slept in their houses. I have walked those farms end to end with the producers. I have memorized every corridor formed by their trees. I have learned their stories.

We have a personal bond such that I can make any specific request on the standards that any specific batch must meet; and they can ask me for help or advice immediately whenever things are not going as planned or an unexpected event has happened.

One of the best byproducts of my research has been the very strong personal relationship with each and every one of the coffee producers I work with. We have spent so much time together that they know for sure that they don’t need to hide anything from me and that I reciprocate by understanding the importance and the value each bag of coffee represents to them.

This amazing result of friendship and trust, focused on excellence, is what Traceability or Specialty Coffee mean to me. Two concepts that are two sides of the same coin.

Specialty Coffee is knowing who produced my coffee and where it comes from; and through this combination understanding that coffee has the ability to reflect the characteristics of the place it comes from and the personality of the people who produced it.

It occurs that in my case practice came first and the vocabulary to define it came later.

What does Organic Coffee mean to me?

Lessons learned from farming coffee in Antigua Guatemala.

My name is Josué Morales and I have been in the coffee industry since 2003. Seventeen years ago, I was absolutely skeptical about organic coffee and about organic agriculture in general.

Lessons learned from farming organic coffee in Antigua Guatemala.

My name is Josué Morales and I have been in the coffee industry since 2003. Seventeen years ago, I was absolutely skeptical about organic coffee and about organic agriculture in general.

Today I am in charge of the production and all the processes at Beneficio La Esperanza and Finca El Pintado. Two farms under the management of Los Volcanes Coffee, which are not only Organic Certified Estates in Antigua Guatemala, but also the only organic coffee produced in this region. These farms are the leading research and testing grounds for organic agriculture in the whole country.

Since 2016 our leadership in the organic arena has made it possible to implement the principles and processes developed in Guatemala, in coffee farms and production facilities in Brazil. Fazenda Pilar, in North Paraná, and Fazenda Rio Brilhante, in the Pantano Micro Region of Cerrado, in Minas Gerais are rapidly adopting the methodologies that we developed in Guatemala.

As good as it sounds, the story behind my change of sides, from being almost against organic anything to being a leader in organic coffee and organic agriculture is not precisely a pretty one.

In the beginning, my approach to coffee was exclusively about the quality of the cup. How that coffee was grown and produced was of little to no importance to me, as long as the coffee presented the characteristics that were being the most valued by an emerging market that rewarded cup score above everything else.

About ten years ago, in the early 2010’s, Guatemala and most of Latin America was severely impacted by the Leaf Rust or “Roya”, a fungal disease that makes a host out of coffee leaves, restricting its ability to perform photosynthesis, and therefore affecting the production of the plant –and even its survival.

Coffee Leaf Rust.

The quality of the cup –the only thing that mattered to me at that time– was deeply affected, and that was the huge red flag that signaled to me that there was something important that I was not paying attention to. In order to survive, I had no other choice but to start considering options that I would have never considered before.

I visited each and every coffee producing region in Guatemala, I traveled to as many other coffee producing countries as I could, I gathered as many ideas as possible. I was considering every idea that existed.

After what I considered an exhaustive process of ideation, I was ready to move on into the next stages: prototyping and testing.

Beneficio La Esperanza, in Antigua Guatemala, became my testing facility. It’s a small farm of five and a half hectares (about 13.5 acres) planted with assorted varieties of coffee, from rust resistant, to rust tolerant, to highly vulnerable to rust.

The first few years can only be described as massive failures. We experienced a severe and extended drought and the first frost in thirty years. And on top of that, the resistance to a change in managerial style was heating things up even more.

This farm had been managed by the previous team in the same conventional way for more than thirty years and all of a sudden I was introducing new divisions, new processes, new combinations, new expectations –new everything! It was nothing but a surprise that an organizational culture turmoil would become an additional ingredient in the mix.

In the middle of those circumstances, we divided the farm in identical sectors where different agricultural practices were tested. Many combinations were tested. High nutrition. Low nutrition. High conventional fertilizers. Low conventional fertilizers. No fertilizers. You name it.

Every single indicator used to measure our success was a disaster. Cup quality, yields per hectare, production per plant, fruit density, and foliage health were all a disaster.

The whole farm was at a point at which nothing could make things worse.

And that’s exactly what I did: nothing.

The rainy season of that year came and went. Shortly after, I clearly remember my first walk through the farm. As I was struggling to make my way through weeds and grass that had grown taller than the coffee trees –and of course taller than me– I made the discovery that changed my perception of coffee production for good.

The coffee plants were surprisingly productive and they were suspiciously healthy underneath the surrounding overgrowth. All my experiments had failed and during the worst part of the leaf rust crisis, the farm was still in better shape than those of most producers in the country.

After clearing the farm from the overgrowth, it was obvious that giving the land a rest had been extremely beneficial for the coffee trees.

Much like us human beings, sometimes all the plants need is a rest. Especially after being asked to be productive all the time for so many years.

Passing this wisdom forward to our team and to our employees was a breeze! Deep down inside, all of them already knew that if they were surrounded by an environment that would make them healthier and stronger, they would naturally be more productive. Why would the plants behave any differently? It’s evident for them as it is for any of us that, after all, we are alive!

That year, the productivity of each tree was way above average, the quality of the harvested cherries was uniform, and the quality of the cup was outstanding.

The conclusion to which I arrived was inevitable: leaving nature alone to form its natural self-balancing systems and to carry its natural processes has no substitute.

It’s from this simple but profound insight that I learned my own definition of what organic agriculture really is, and it’s based on this definition that I have designed, created, and implemented the agricultural processes and methodologies that have allowed me to become a leader in Organic Coffee Production in Guatemala, and soon in Brazil too.

Organic agriculture is a system that sustains life, health, and the structure of soil.

As you probably noticed, this is a positive definition, not a negative one, as is the belief of many producers.

My definition of Organic Coffee Production says yes to life, says yes to health, and says yes to the natural structure of the soil

Most other definitions out there are negative. Some claim to be organic coffee producers because they say no to herbicides. Some claim to be organic coffee producers because they say no to fungicides. Some claim to be organic coffee producers because they say no to synthetic pesticides. Some claim to be organic coffee producers because they say no to Growth-Promoting Antibiotics. Some claim to be organic coffee producers because they say no to GMOs.

I bet you can easily tell the difference between their definitions and mine.

I say yes to nature. I say yes to life. I say yes to health. That is what has made all the difference in my production. That is what has made all the difference in my methodologies. That is what has made all the difference in myself, as a human being.

That our coffee has an outstanding cup quality is a fact, but it’s not my main objective –let alone my sole objective– anymore. It’s just a byproduct of caring about nature, caring about life, and caring about people.