What does Human Centered coffee production mean to me?

The weakest link in the supply chain is also the strongest one.

The Valley of Nebaj in Quiché, Guatemala. October 2006.

When I was growing up, my father thought that I had to get to know every single municipality in my country, Guatemala. At first glance, this seems like a feasible idea, even an exciting idea. But in the 90’s Guatemala was still a very remote country, severely underdeveloped, most of it with precarious or even non-existent infrastructure, and living through the last wave of the Civil War.

This was not just about the geography and the numerous paradisiacal landscapes. This was also about the people. About 76% of the population is divided into 22 ethnic groups of Mayan descent, each with its own language, its own customs and traditions, and, as I would learn years later, with their own particular ways of going about business.

My favorite place was –and is still to this day– Panajachel, a small town located on the shore of Lake Atitlán. Or “The Lake”, as tourists call it. About 18km long and 8km wide (11.2 x 5 miles), a maximum depth of 340 meters (1,120 ft) makes it the deepest lake in Central America. It’s framed by three stunning volcanoes, all higher than 3,000 meters (10,000 ft), and surrounded by lush forests in every direction. It’s not only my opinion that this lake is beautiful. Alexander von Humboldt literally called it “the most beautiful lake in the world.”

Panajachel is an absolutely magical place. It’s decorated with some of the most amazing sunsets I’ve ever seen, and also with the most diverse of populations, as uniquely colorful as the sunsets themselves. This is the place that congregated most of my extended family.

Visiting my grandparents was a whole different story. They lived in the eastern part of Guatemala, which is as hot and arid as a land can be without being properly a desert. Just as the environment is different, life is also different. In this cracked and dusty soil, the vegetation is very peculiar, often more brown than green and full of huge thorns. There are always vultures flying high against the sun in circles.

These two were the most recurrent places. From here we would make camp and move on to other more remote areas that could only be described as part of a fairy tale book. I spent all my childhood and adolescence going on these expeditions.

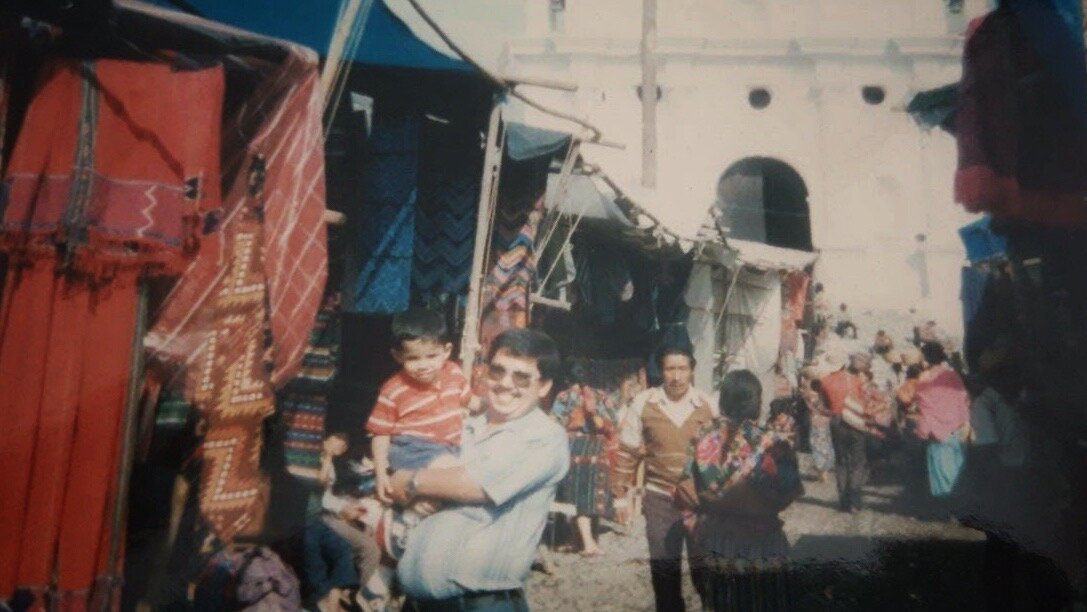

My father and I at the market of Chichicastenango in Quiché. Guatemala, 1989.

When I reached adulthood, I was very familiar with even the most remote places in my country. I knew how to find and drive through the most incredible secret roads. I knew how to maneuver through the many extreme microclimates that change drastically from one kilometer to the next one.

But living all these experiences meant much more than just appreciating the astonishing scenery Guatemala has to offer. It meant experiencing how people live in each part of the country. It meant hanging out with locals in each town and sitting in the square just watching time go by. It meant having dinner and chatting long hours at the tables of friends and going to mass with them on Sundays. It meant experiencing and learning how differently the very same activities were carried out between one place and another.

It involved talking to people. A lot. Asking for directions. From how to get to a place, to where to catch the sunrise or the sunset. Listening to stories and legends. Paying the most careful attention to the advice given by the elders.

I discovered that this small country was a very big world.

One of the last places I visited was the northern part of Quiché. Perhaps the most severely hit by the terrors of the Civil War, where the worst of the massacres had occurred. The type of unspeakable contradictions that make these lands cry tears of blood.

I had read about these places in history books and in reports from the United Nations. The names always seemed to me like places that had been ravaged by war and were deserted to the point of being wastelands.

To my surprise, places like Cunen, Salquil, Acul and the whole region known as The Ixil Triangle, formed by the towns of Nebaj, Chajul and Cotzal, are among some of the most exuberant and breathtaking places I’d ever been to.

The drive to Quiché is a rollercoaster. Up and down the most complicated road in the country, with its sharp turns barely hanging from cliffs, with potholes in every section of the way, and, now and then, tons of pouring rain. At some point you reach Sacapulas, which is so low in altitude that it feels as if you’re in a beach town in the middle of the mountains. From here it’s all uphill into the clouds.

I would drive this road on a Friday afternoon. Feeling how the weight of the “things of the City” gradually stayed behind until they disappeared completely. Ten to twelve hours later, depending on the weather, I’d be sleeping in Nebaj.

On Saturday, the noise of a very busy street outside my window would wake me up. After sunrise, under the faint but constant rain, I would walk two blocks down towards the square to have breakfast, down the steps in a corner into a diner called Comedor Elsim.

One of the strongest impressions I have of Nebaj was coming out of this comedor, thinking already about the drive back to the city, when I saw a large group of people gathered in the middle of the street. There was a man holding a stick in one hand and a rattle toy on the other. In front of him, on the ground, was a brown piece of cloth. The crowd was absolutely silent as he danced around it in circles holding the stick and rattling the toy. Underneath the cloth was a snake. As the serpent enchanter whistled there was thunder in the distance. Downhill, a tent was being set up. The circus had arrived in town. The year was 2005.

I felt a strong affinity towards the Ixil people I had made friends with. The leader of this one group, called Joel, had told me how he survived two massacres while he was still only a kid. He was always looking for ways to do business and bring projects to his community. A sense of community that can only be understood in light of the terrors of their past.

Once a month I would drive up to Quiché with my father, who is still to this day my guide and companion when going to these difficult places in Guatemala. We would have meetings with a group of people who were trying to get organized to form a Cooperative so that they could be beneficiaries of some government program.

This was my first attempt at working with a community, and my intention was to document how many members they had, where their parcels were located, how many coffee trees they had in these parcels, and how much coffee was produced.

This was also the first time that I was trying to adapt my Coffee Traceability System to follow collective decisions instead of the individual decisions of single producers.

As I interviewed them, with a translator interpreting my questions, my father would snap their portraits, one by one, and we would make them name tags as a symbol that they were part of the project, although the pictures were mainly visual aids for me so that I could remember their names.

Portraits of Members from the Ixil Community in Nebaj. November 2005.

The idea was simple: if my system was working on larger farms to trace the samples back to their handling, back to their harvesting, and even back to the growing of the coffee trees, then it would also work for a group of producers if I treated the Cooperative as a single large farm and I just added one additional line to register who the individual producer was.

With my system in place, I would have all the information necessary to advise each producer individually on how to improve their practices so that their samples would result in a better taste of the cup. With time, they would end up delivering beans of such a quality that I could roast them to an extraordinarily above average cup quality, just like I was doing with the larger farms.

(Read: What does Specialty Coffee mean to me?)

I’ve always preferred working with people with whom I have a strong friendship. The relationship was there. I’ve always preferred working with people that are eager to learn and to excel. This hunger was there. We had spent months planning and getting ready to solve any issues that might arise along the way. The preparation was there. My Coffee Traceability system had been adapted to their Cooperativa. Everything was there!

Harvest came and not a single coffee sample was sent to me.

By the time I went back to the mountains, all of the harvest had been sold to someone else.

Sitting with them at Comedor Elsim, I was trying to have them explain to me what had happened. We had spent nearly a year working together so that in the end I would receive their samples and I could taste their coffee. And in the most critical moment of the whole process, nothing happened.

What went wrong?

All along the way, I had been paying attention to how to make things work. But I had overlooked how people work.

These people had learned for generations to act from fear before anything else. So when a swiss guy came to the community waving the Fair Trade flag and offering to pay sub-par prices up front, they sold. They sold everything. They sold everything to less than half the price that I was offering to pay because they were not comparing prices. They could only put certainty on the scale. And with only certainty on their minds, a very low price up front was undoubtedly better than the promise of a higher price that I had offered to pay at the end of harvest.

Up to this day, I still consider my project in Quiché to be my biggest failure. But it’s also the failure from which I learned the most important lesson of my professional career: things will only work if you truly put yourself in the shoes of the people that you’re working with. Not just a bit. All the way! Until the point where you deeply understand their feelings and emotions and take care of that first.

After you have taken care of their feelings and emotions, then you can take care of their interests. Then you can talk business. Then you can start doing business, and actually succeed.

It’s only after you have taken care of their feelings and emotions that each and every one of those individuals become the strongest link in your supply chain.